Devlog 0: SPAAAAAAAAAAAACE

I love space. I want to make a space game, but making a space game comes with one big challenge:

space

is

BIG

So if we’re trying to basically make all of SPACE, how exactly do we store the position of anything? And how do we make all those stars?

The Naive Approach - direct storage

We we can store any position as a 3-dimensional vector (Vector3), surely we can just use that, right? This brings us to our first villain of our devlog: floating point representation.

Floats are the main way computers store numbers. They’re great because they can store really really big and really really small numbers. Put (very) simply, they let us move the decimal point around

9023784562309.456

imagine we have this number

9023784562309.456

^

we can pick up and move this decimal

0.00000000009023784562309456

^

over here

902378456230945600000.0

^

or even over here

You may already see the catch: While floats can put the decimal point pretty much anywhere, they have fixed precision.

902378456230945600000.0

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

we can only have this much data, so even though we moved the decimal

902378456230945600000.0

^^^^^^^

we've still got all these zeros over here

The further away we are from zero, the less exact our numbers gets. This has a big impact on physics and rendering, and every game with a super big map has to deal with this.

There are a few different ways that other space games deal with this problem.

Outer Wilds keeps the player at the very center of the game world. Every time you jump, the entire universe moves out from under you (trippy, right?). This works very well for the small solar system the game is set in, and could theoretically work on a larger scale. The big problem comes when doing collisions: you have to take the velocities that are imparted on the player and instantly impart them upon every object in the game. I’ve tried this in Godot in the past. In principal it should work but in practice it introduces more than a few collision bugs. We also still have to store the position of everything using floats, so we can’t have objects lightyears away.

No Man's Sky doesn’t really let you explore an entire universe. It breaks everything up into sections. You don’t actually fly to a nearby star, you enter a loading screen and enter a new scene with anther sun and set of planets. I don’t want compromises like that. I want to travel between stars with real distances and velocities. You should be able to look up at the sky and travel to any star you see. No Man’s Sky does do some interesting stuff for representing the scale of planets and stars but we’ll talk about that in another devlog.

I settled on a third solution:

Cells

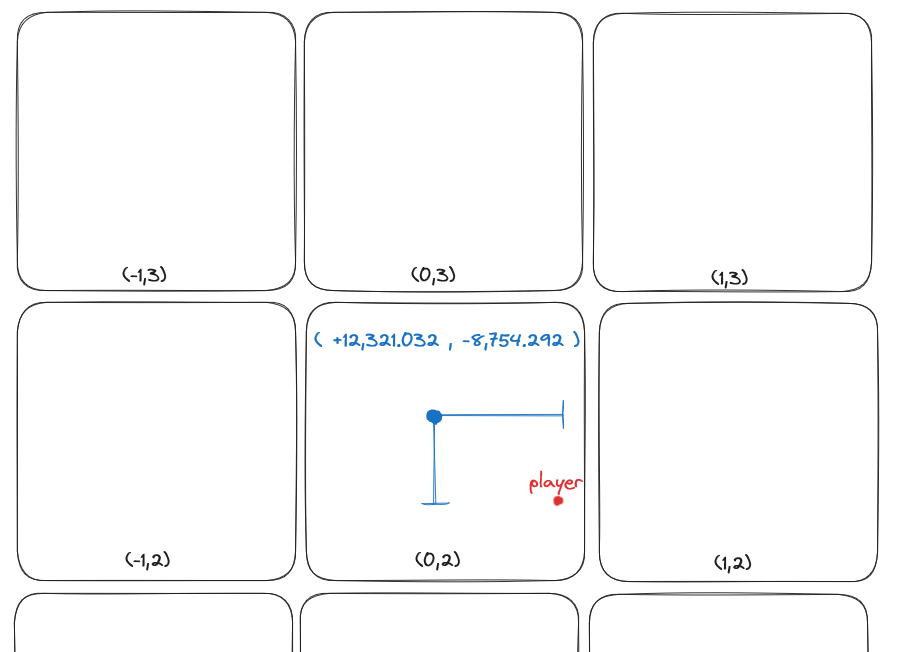

We could divide the world into chunks (I’ve been calling them cells). We can store our position as a set of two values: A 3d vector of integers that describe what cell we’re in, and a 3d vector of floats that tells us where inside the cell we are.

Every time our player gets to the edge of the cell, we can increment to the next cell and wrap our floating-point position. This also solves another problem: I don’t want to have to place every star, planet, or space station by hand. Even if I could, the amount of storage space I would need in order to save all of that data would be immense. Using cells means we can easily generate and place objects based on the cell we’re in. This also means that if our player hits the edge of the universe, they’ll wrap around automatically from the integer overflow.

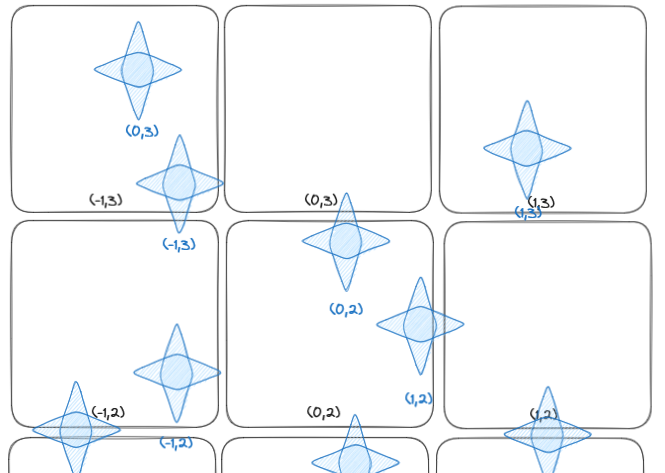

Here’s an example where every cell has a star:

But this looks super boring. Let’s add some random data to this.

We can offset the stars by varying amounts to hide our grid from the player. Every star is still technically at the same position as before, but we can offset the rendering. But where do we get this random data?

Random Generation | Attempt 1

We need our random numbers to be deterministic, meaning if we generate a star for cell (1, 4, 2), that same star should be in the same position every time we generate it. To do this, we need to set the seed of the random number generator. The seed is the value that a random number generator starts with to make random numbers. This means that if we put the same seed in every time, we’ll always get the same result. But how do we get the seed?

Theoretically we can store integers (whole numbers) anywhere from negative to positive 18,446,744,073,709,551,616. But we’re using 3 of these numbers for every single cell, how do we plug that into a seed function?

There is a very clever way you can deconstruct a 2d array into a 1d array.

our 2d array

[

[0,1,2],

[3,4,5],

[6,7,8]

]

we can access every value using two numbers

[y][x] -> value

[0][0] -> 0

[2][1] -> 7

we can turn this into a 1d array

[0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]

id = x + 3y

if [0][0] -> 0

then id = 0 + 3(0) = 0

if [2][1] -> 7

then id = 1 + 3(2) = 7

so we've deconstructed this into a 1d array, but we can still get

to every value using the same x and y as before

we can also do this for 3 dimensions.

the formula becomes x + 3y + 9z.

the general form of this is x(size^0) + y(size^1) + z(size^2),

where size is the size of your 3 axises

So, if we know the size of our grid beforehand, we can take any 3 numbers and get an entirely unique value.

Success! (with some caveats)

Seeds only take in integers, so we’ll have to tune our formula carefully. If we didn’t put any limit on the size of our world, then our formula would produce numbers beyond the integer limit. This would overflow the integers (an integer goes beyond its maximum value and returns to zero) and could produce sections of the universe exactly identical to other sections. We also can’t have any negative numbers. The formula assumes that all inputs are positive integers. Negative numbers would, like integer overflows, give us multiple paths to the same value. To keep all numbers positive, we wrap the cell position once it reaches our size or dips below zero.

This limits us to a scale of about 2,642,245 cells across in each direction. This is a pitiful amount, and it’s slow to calculate this value for every star. We can do much much better.

Attempt 2 | Random Noise

I have a confession: The last method was what I used primarily for a large portion of the project. The following attempts are after a break from the project, and redoing all the code:

Godot has a noise generator, and it’ll let you generate 3d noise. This noise gives us random numbers and more importantly, is super fast. We can call it 27,000 times easily during startup without creating a large slowdown. But there’s one detail I was forgetting.

This is the function in my code that gives each star its random position. It takes in the cell position (Vector3i), and returns an offset for the star (Vector3). Take a peek and see if you can find the issue with this code. You may need to reference the Godot docs for this.

func StarNG(cell_position: Vector3i) -> Vector3:

var rand = RandomNumberGenerator.new()

var noise = FastNoiseLite.new()

#seeds our random number generator

#our random number generator takes integers as seeds,

# but noise returns a float between 0 and 1

#we multiply by 100000 so our seed isn't just rounded to 0

var noise_seed = noise.get_noise_3dv(cell_position) * 100000

rand.set_seed(noise_seed)

#generates an offset

var vector_out = Vector3()

vector_out.x = rand.randf_range(-1, 1)

vector_out.y = rand.randf_range(-1, 1)

vector_out.z = rand.randf_range(-1, 1)

return vector_out

Here’s your hint, which doubles as part of Godot’s documentation:

● float get_noise_3dv(v: Vector3)

Returns the 3D noise value at the given position.

We’re using two different types for most of our code, Vector3 and Vector3i. Vector3 is a 3d vector of floats while Vector3i is a 3d vector of integers. We can convert between the two, but this can lead to issues with precision. If we take a float and convert it to an integer, we lose everything after the decimal point. If we take a really big integer and convert it to a float, we could lose some of the data close to the decimal point. (This is your last chance to figure the problem out for yourself if you haven’t already)

We’re using 3d noise to generate our seeds, but this noise function doesn’t accept a Vector3i, it takes in a Vector3. This means if our player went super far, to the edges of our universe, they might start seeing repeating stars as we lose floating point precision. This is why knowing exactly what goes in and comes out of your functions is super important. I didn’t even notice this issue (and probably wouldn’t’ve) until an unrelated bug brought my attention to this problem.

Attempt 3 | The Regrettably Obvious Method

Here’s the solution that is now in my code

# fixed seeding algorithm

rand.set_seed(cell_position.x)

rand.set_seed(cell_position.y + rand.randi())

rand.set_seed(cell_position.z + rand.randi())

We seed the RNG object by feeding it each part of the cell position summed with a random number seeded by the previous step. This ensures that if even one part of the cell position changes by a single value, we’ll have an entirely different value. I will acknowledge the obvious issue, this still leaves us only with as many stars as 32-bit integers. This is true, but we can continue to feed in parts of the cell position to seed other attributes of the star and its orbiting planets (I hope to go in depth at a later point when I get to planets).

A Final Task

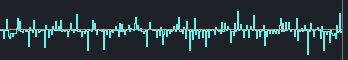

While the randomization is no longer an issue, we’re still moving thousands of nodes every time we wrap the player back around. Here’s a graph of my frame time, every dip above the red line is where a frame took too to process (didn’t meet 60fps).

I’ve tried using MultiMeshInstances, which moves the stars to the GPU instead of being purely handled as nodes by the CPU, but I still need to do too much work with the CPU for this to save any performance. The other option was to move the parent of the stars instead of each individually, but surprisingly this doesn’t run faster either. One option left is to “render” the stars by hand (which isn’t off the table). The other is to write some of these scripts in a more performant language like Rust. My end goal is to have about 5 thousand stars at once. But this method is still fast for smaller star counts. Numbers under about a thousand don’t have any issues.

For now that’s good enough! Sorry for the super long blog post, I’ll try to keep the next one a bit shorter, but I hope you enjoyed reading it! If you have any recommendations for optimization, feel free to send them my way!

If you haven’t already, join my discord server to get updates on the stuff I make online, and notifications for when I post next. You can also find news there about The Jam! An event I host occasionally where you can submit any type of art (that’s right, any). If that sounds interesting then head on over and take a peek, I don’t always have time to host stuff like this so check it out while its running.

That’s all for now! See ya!